Hay Time!

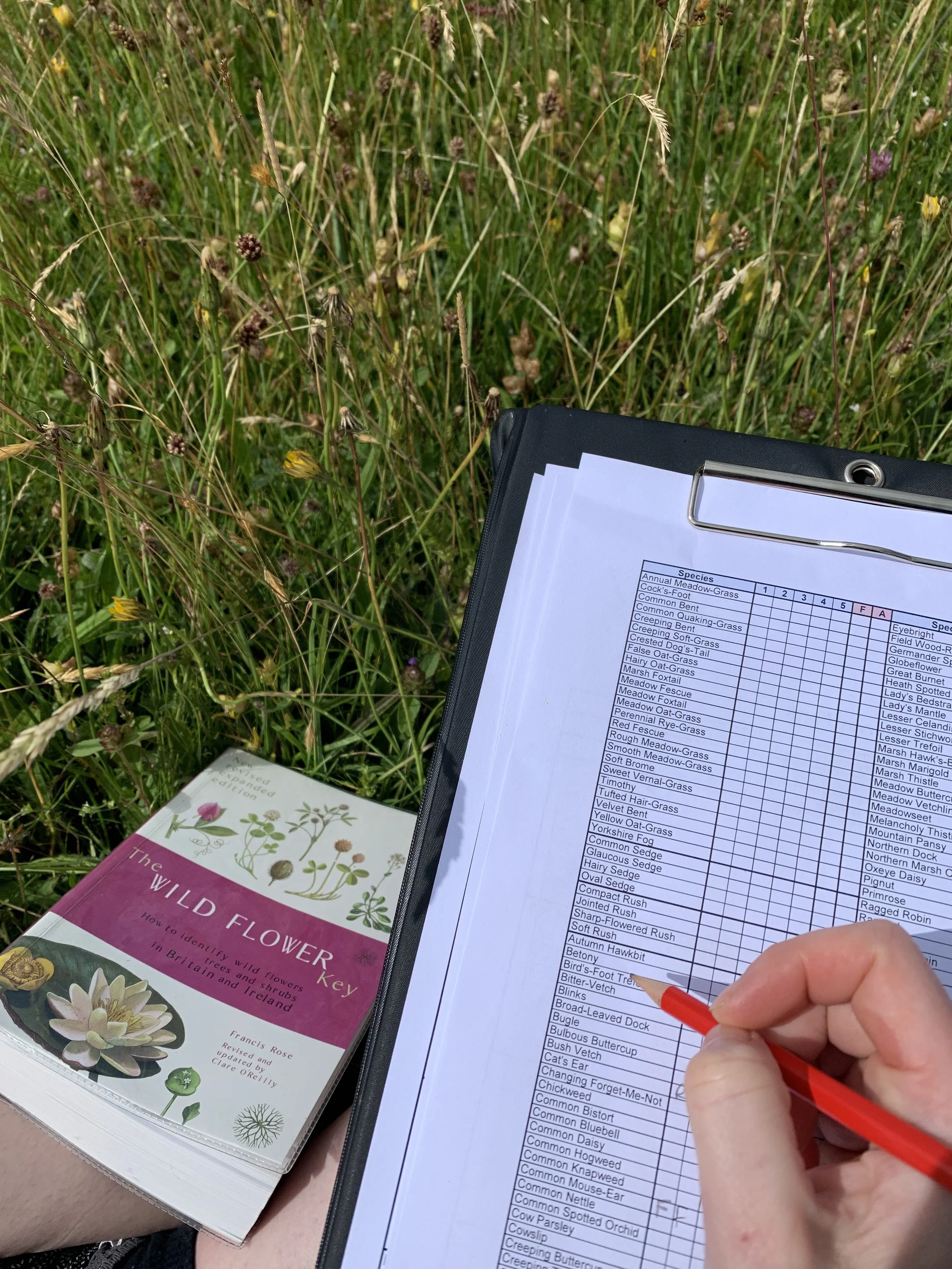

In July of 2023, I volunteered on my first meadow survey with The Yorkshire Dales Millennium Trust’s Hay Time project. I had attended the training day and turned up to my survey armed with my Francis Rose Wildflower Key and a beginner's enthusiasm. I had a few niggling doubts about pulling my weight but was In good hands with Cath, ‘Bee Lady’ and Hay Time project leader.

To meadow a meadow

A little research beforehand revealed that I had some misconceptions about meadows and what they are, so I was keen to quiz Cath on this as we moved between our survey locations. It turns out it’s as much a verb (to meadow) as it’s a noun (a meadow). This fact became clear to me as I listened to Tom (the farmer) discuss with Cath how he might go about ‘meadowing’ this field or that. I suppose I’d just thought that if a field has long grasses and a few flowers growing therein, then it must be a meadow. In my idealistic, nature-loving naivety, I had also once assumed that the best meadows would be mostly free from human intervention and the result of nature being left untouched. But I was wrong on both counts. Meadows are, it turns out, a collaborative effort between humans and wildlife, and we have been ‘meadowing’ since the Iron and Bronze Ages (English Heritage). The traditional, time-honored method follows a low input rhythm of cutting, strewing, and grazing with zero inorganic input. This method maintains the biodiversity of the meadow because it prevents the domination of any individual species, making them high-value, priority habitats. A single, well-managed meadow has the potential for up to 120 species of wildflowers, supporting a vast range of animal life. Furthermore, species-rich meadows absorb more carbon than those species-poor and reduce flood risks (Hay Time Final Report, 2012).

Why Hay Time?

Due to intensive agricultural practices stimulated by government pressure and subsidies, we have now lost 97% of our meadows in the UK. Maybe like me, you need a moment to digest that percentage because it’s difficult to comprehend! But don’t be discouraged. It is possible to mitigate the loss of our hay meadows as the Hay Time Project, which began in 2006, has already proven. The project aims to restore upland and lowland meadows in and close to the Yorkshire Dales National Park working closely with farmers to target restoration using locally harvested seed. One of the fundamental aspects of the project is that It created a system of donor and receptor meadows where the seed is collected from species-rich meadows and donated to those which are species-poor. Surveys are then regularly carried out to track the progress of biodiversity and continue to inform their management.

Our Survey

One of the first things I learnt about the meadows we were surveying was that they were donor meadows. Something about this just speaks to my sensibilities. I found myself quietly thanking the meadow for its service. How wonderful that when we take the care to nurture one meadow, that meadow can take care of many others, and so on and so forth. That’s the kind of exponential growth I can get behind!

The second thing that became apparent was the glorious quantity of yellow-rattle present there. Yellow-rattle, Rhianthus minor or hay-rattle is a stunning wildflower with a uniquely sculptural formation. One of its gifts is that when it goes to seed, the pods give a delightfully audible rattle (hence the name). Another of its gifts is its unique role in the meadow's ecosystem. Unfairly in my view, It’s often considered a parasitic plant. However, it is a star player in meadow restoration and conservation. Keeping the growth of more vigorous grasses in check and giving more wildflowers a chance to establish - what a team player!

We recorded 19 species in total (though there were many more across the farm and in other meadows we didn’t survey that day). They were, in rough order of frequency:

Hay/Yellow rattle, Rhianthus minor

Ribwort plantain, Plantago lanceolata

Rough Hawkbit, Leontodon hispidus

Cats Ear, Hypochaeris radicata

Eyebright, Euphrasia agg

Red clover, Trifolium pratense

White clover, Trifolium repense

Common mouse ear, Cerastium fontanum

Autumn Hawkbit, Leontodon autumnalis

Meadow Buttercup, Ranunculus acris

Pignut, Conopodium majus

Selfheal, Prunella vulgaris

Yarrow, Achillea millefol

Bluebell, Hyacinthoides non-scripta

Lesser trefoil, Trifolium dubium

Meadow sweet, Filipendula ulmaria

Common Hogweed, Heracleum sphondylium

Ragwort, Senecio jacobea

Daisy, Bellis perennis

Farmer Tom

After we finished our survey, Tom offered to show us the other meadows. I have always been fascinated by people who steward the land, so I was glad of the opportunity to talk with Tom as he guided us through his meadows.

As we walked, I couldn’t help but notice how Tom moved slowly and intentionally. When speaking or answering a question, he would stop and give his whole presence to it. There was no rushing or hurrying through a conversation, which I appreciated. He was keen to show us how each meadow had its distinct characteristics, pausing to point out particular species that seemed happier to inhabit some areas and saying things like, “Can you see? The hawkbit is coming out a bit later in this one,” and, “Did you spot the self-heal over there?” For my benefit as a botanical dyer, he kindly pointed to the lady’s bedstraw as a traditional dye plant. Of course, I was won over (as if I wasn’t already!)

He discussed with Cath how he planned to go about things differently in different meadows, “Maybe I’ll just graze this one, maybe I’ll mow the other, or perhaps I’ll just let it be for now.” As a steward of donor meadows, he was keen to know how the other farms were getting on with his seed and was intrigued as to why the sheep didn’t seem to enjoy nibbling the yellow-rattle so much as the other flowers. It seemed to me that Tom had a curiosity for the living world and that much of his decision-making was rooted in an intuition that comes from paying close attention to it. I asked him about this intuitive approach to managing the land. He replied, “Everyone always seems so concerned with this idea of ‘managing’ the land with these rigid ways of doing this or that at particular times. But it’s more complex than that. It’s certainly not how things used to be.”

Thinking of ‘how things used to be,’ I remember that shocking statistic of the extent of our meadow loss and wonder if it would ever be possible to recover what we have lost. Though we may never be able to restore our meadows fully and to their original state, we can undoubtedly nurture that indefatigable curiosity that Tom has for the living world, and through projects like Hay Time, we can reimagine new futures of working again in collaboration with it. In 2022 YDMT reported that “38 hectares of hay meadows were regenerated, increasing biodiversity and providing a vital food resource for pollinators and other insects,” (YDMT, 2022).

On that hopeful note, I’d like to leave you with this anecdote from Tom. On our way back through the farm, he spoke of how his grandfather made hay using the traditional long Roman scythe. He reminisced about how as a young boy, he would follow behind his grandfather as he moved in the slow and steady rhythm of scything and try to catch the meadow brown butterflies as they fluttered up in his grandfather's wake. As I listened to Tom relay this memory with his long white hair and walking stick and with all his curiosity and wonder at the living world, it wasn’t a stretch to picture that young grandson chasing the meadow browns through his grandfather's meadow.

How you can help

If you’re wondering how you can help beyond getting directly involved with meadow surveys, below are two ways you can contribute financially to the work of the Yorkshire Dales Millenium Trust.

Give a living bouquet: https://www.ydmt.org/wildflower-gifts

Donate to YDMT: https://www.ydmt.org/donate

References and further reading:

https://www.ydmt.org/what-we-do/landscape-and-wildlife/wildflower-meadows

https://www.yorkshiredales.org.uk/about/wildlife/projects/hay-time-project/

https://www.ydmt.org/resources/files/hay-time-final-report.pdf

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/learn/histories/history-of-meadows/

https://www.ydmt.org/resources/images/Impact%20Reports/YDMT%20Impact%20report%202022.pdf